Gynaikothrips ficorum (Marchal, 1908)

Phlaeothripinae, Phlaeothripidae, Tubulifera, Thysanoptera

Figures

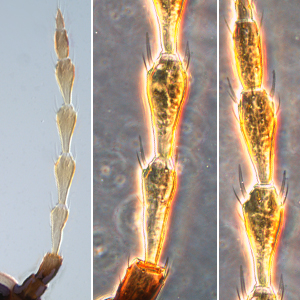

Fig. 1: 8-segmented antenna, segments III and IV with simple sense cones, terminal segments V-VIII

Fig. 2: Head dorsal with ocellar triangle

Fig. 3: Head and pronotum

Fig. 4: Meso- and metanotum

Fig. 5: Fore- and hind wing, fore wing with duplicated cilia

Fig. 6: Metanotum and tergite I (pelta)

Fig. 7: Tergites II and III with wing-retaining setae

Fig. 8: Tergites VIII-XI, tergite X (=tube)

Introduction and recognition

Gynaikothrips ficorum is well known around the world inducing leaf-galls on cultivated Ficus microcarpa. Both sexes fully winged. Body dark brown; tarsi and apices of tibiae yellow (Fig. 5); also antennal segments II-V yellow, VI shaded at apex, VII shaded in distal half and VIII light brown (Fig. 1); fore wings pale with margins shaded on distal half (Fig. 5). Antennae 8-segmented; segment III with 1 sense cone, IV with 3 sense cones. Head longer than wide; slightly constricted behind eyes (Fig. 2); postocular setae with apices bluntly pointed, arising well behind compound eyes, scarcely extending to posterior margin of compound eye; maxillary stylets retracted almost to postocular setae, about one third of head width apart (Fig. 2 and 3). Pronotum with strongly developed transverse lines of sculpture forming conspicuous swirls (Fig. 3); with major setae variable, anteromarginals minute, anteroangulars commonly well developed, posteroangulars never more than 0.5 times as long as the epimerals and usually no longer than the discal setae; epimeral sutures variably complete. Prosternal basantra absent; mesopraesternum broadly boat-shaped; metathoracic sternopleural sutures not developed. Metanotum strongly sculptured with longitudinal reticulations (Fig. 4). Fore tarsus with small or minute tooth. Fore wing parallel sided; with about 15 duplicated cilia (Fig. 5). Pelta broadly triangular, median reticulations with internal markings (Fig. 6); tergites II-VII with 2 pairs of sigmoid wing-retaining setae (Fig. 7); tergite IX setae S1 acute and about 0.8 as long as tube; tube longer than head (Fig. 8).

Male smaller than female; no fore tarsal tooth; tergite IX setae S2 short and stout; sternite VIII without glandular area.

Taxonomic identity

Species

Gynaikothrips ficorum (Marchal, 1908)

Taxonomic history

Haplothrips blesai Plata, 1973

Gynaikothrips flavus Ishida, 1931

Leptothrips reticulatus Karny, 1912

Liothrips bakeri Crawford DL, 1910

Leptothrips flavicornis Bagnall, 1909

Phloeothrips ficorum Marchal, 1908

Common name

Cuban laurel thrips

Banyan leaf-rolling thrips

Present taxonomic position

Family: Phlaeothripidae Uzel, 1895

Subfamily: Phlaeothripinae (Uzel) Priesner, 1928

Genus: Gynaikothrips Zimmermann, 1900

Genus description

The genus Gynaikothrips Zimmermann, 1900

This genus contains 40 species, which feed on leaves and produce leaf-galls or leaf-rolls. Most of these species are found in the Oriental region on tropical or subtropical plant material, but 2 related pest species Gynaikothrips ficorum and Gynaikothrips uzeli are distributed worldwide due to horticultural trade of ornamental Ficus spp. (Mound & Kibby 1998). These are large thrips species with dark bodies, sometimes containing internal pigmentation, and 8-segmented antennae. Members of this genus have 1 sense cone on antennal segment III and 3 on segment IV, and due to these characters is thought to be related to the genus Liothrips.

Species description

Typical key character states of Gynaikothrips ficorum

Coloration

Body color: mainly brown to dark brown

Antennae

Number of antennal segments: 8

Form of sensorium on antennal segments III and IV: emergent and simple on segments III and IV

Number of sense cones on segment III: 1

Number of sense cones on segment IV: 3

Head

Maxillary stylet position: about one third of head width apart

Maxillary bridge: absent

Postocular setae: about half to nine tenths as long as compound eye

Cheeks: without seta-bearing tubercle

Prothorax

Prosternal basantra: absent

Epimeral suture: interrupted

Pronotal posteroangular and epimeral setae: posteroangular seta never more than 0.5 times as long as the epimeral seta

Wings

Fore- and hind wings: present, more than half as long as abdomen

Fore wing veins: absent

Fore wing shape: mainly parallel sided or margins run continuously towards each other

Fore- and hind wing surface: not covered with microtrichia, smooth

Fringe cilia arising: not from sockets

Fore wing duplicated cilia: present

Fore wings: uniformly pale or weakly shaded

Fore wing extreme apex color: pale

Legs

Fore tarsus: without a tooth or hook

Abdomen

Tergites III to V: with two pairs of sigmoid curved wing-retaining setae

Abdominal segment 10: complete tube in both sexes

Similar or related species

Gynaikothrips ficorum is very similar in structural details to Gynaikothrips uzeli. The only reported difference between these two species is the length of the pronotal posteroangular pair of setae. In Gynaikothrips ficorum, these setae are never more than 0.5 times as long as the epimerals and usually no longer than the discal setae, and in Gynaikothrips uzeli, they are at least 0.7 times as long as the epimeral setae, and always longer than the discal setae. A more practical, but less accurate, way to distinguish Gynaikothrips uzeli from Gynaikothrips ficorum is by host plant association. Mound et al. (1995) suggest that Gynaikothrips uzeli is the primary gall maker (i.e., leaf folder) on Ficus benjamina, whereas Gynaikothrips ficorum is the primary gall maker (i.e., leaf roller) on Ficus microcarpa. Mound, Wang & Okajima (1995) suggested that Gynaikothrips ficorum is probably a form of Gynaikothrips uzeli that has been widely distributed by the horticultural trade. Further studies, especially on the ITS-RFLP-patterns of these two species should clarify the species state, but first results show very similar patterns of DNA-fragments using both "sub-species".

Compared to other members of Phlaeothripidae, species of Gynaikothrips have parallel sided fore wings (other species with fore wings distinctly constricted medially, only Karnyothrips flavipes with weakly constricted fore wings). Almost all species have a mainly brown body color, uniformly fore wings, and tergites II-VII each with 2 pairs of wing-retaining setae (only Aleurodothrips fasciapennis with a bicolored body, fore wings with transverse alternating bands of dark and light, and tergites II-VII each with 1 pair of wing-retaining setae), and no seta-bearing tubercle on cheeks (only Hoplandrothrips marshalli has cheeks with at least 1 seta-bearing tubercle in basal third or 3 pairs laterally). Species of Gynaikothrips are similar to Karnyothrips flavipes and species of Haplothrips in having having their maxillary stylet apart by about one third of head width apart, and the length of postocular setae is about half to nine tenths as long as eye (in Aleurodothrips fasciapennis the maxillary stylet position is more than half of head width apart, and postocular setae are shorter than distance of the setal base from the compound eye; in Hoplandrothrips marshallithe maxillary stylets are about one fifth of head width apart, and postocular setae are as long as dorsal length of compound eye or a little longer). Species of Gynaikothrips as well as Hoplandrothrips marshalli and Aleurodothrips fasciapennis have neither a maxillary bridge nor a prosternal basantra (Karnyothrips flavipes and species of Haplothrips with maxillar bridge and prosternal basantra). Like Hoplandrothrips marshalli, Karnyothrips flavipes and Haplothrips (Haplothrips) gowdeyi, species of Gynaikothrips have duplicated cilia on posterior margin of fore wing (Aleurodothrips fasciapennis and Haplothrips (Trybomiella) clarisetis without duplicated cilia on posterior margin of fore wing).

Biology

Life history

Life cycle from egg to adult takes 2-4 weeks (Denmark et al. 2004) and all life stages can be found within the galls or rolls of the leaves.

Host plants

Ornamental laurel plants, figs like Ficus microcarpa and F. retusa.

Vector capacity

None identified, but possible mechanical distribution of phytopathogenic fungi and bacteria.

Damage and symptoms

Adult thrips use their rasping-sucking mouthparts to feed on the tender, light-green leaves, causing sunken purplish red spots along the midrib. Tight curling of the leaf is caused by feeding from the developing colonies of immature thrips. The curled leaf becomes hard and tough, then gradually yellower and browner, and drops during windy, rainy weather. Heavily infested leaves eventually become tough and brown or yellow (Denmark et al. 2004).

Detection and control strategies

Biological control: Several insects have been reported as predators within these galls, including Orius and Macrotracheliella (Anthocoridae), Baccha (Syrphidae), and Tetrastichus (Eulophidae), also mites of the genus Pyemotes (Mound & Marullo 1996). Dozier (1926) reported two species of Anthocoridae (minute pirate bugs), Macrotracheliella laevis and Cardiastethus rugicollis, to be predacious on these thrips in Puerto Rico. Montandoniola moraguesi was introduced into Hawaii (Funasaki 1966) and Bermuda (Bennett 1995) as a biological control agent. It was detected in Florida in 1990 as an immigrant species (Bennett 1995). Stock from Florida was shipped to Texas in 1992 as a biological control agent (Bennett 1995). Other biological controls include green lacewing larvae, bigeyed bugs, damsel bugs, ladybird beetles, predatory thrips, parasitic wasps, predatory mites, and Verticillium (a fungal pathogen) (Padrick 2004).

Cultural control: Replacing F. retusa with a resistant species of Ficus probably would be the best and most lasting control of this pest. Because the Cuban laurel thrips only attacks the tender new foliage on small plants, it should be possible to prune out the new growth and eliminate the thrips population. Consequently, there is no suitable foliage for feeding and oviposition and the infestation should die out before new growth emerges (Denmark et al. 2004).

Additional notes

The Cuban laurel thrips, Gynaikothrips ficorum, is well known around the world inducing leaf-galls on cultivated Ficus microcarpa, having been distributed by the horticultural trade with its host plant (Mound et al. 1995). The laef galls induced by this species commonly enclose several other insect species, including various parasitoids and predators of the thrips (Mound & Kibby 1998).

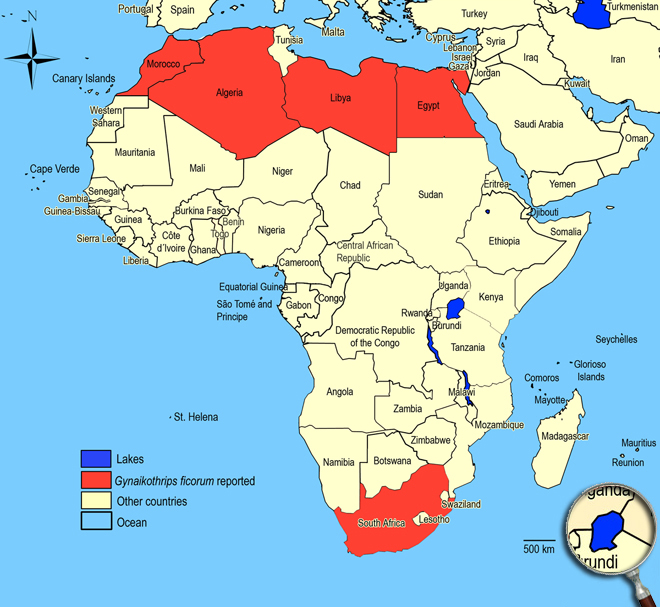

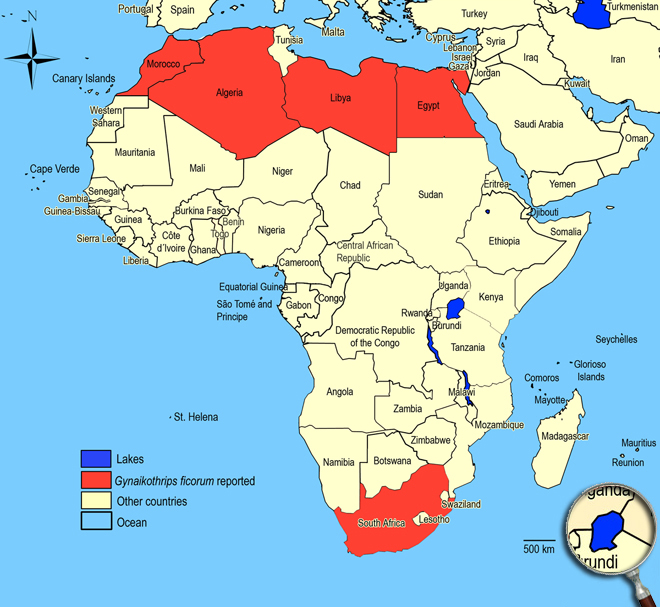

Biogeography

Worldwide in tropical and semitropical areas outdoors, in greenhouses in temperate areas.

Algeria,

Egypt,

Libya,

Morocco,

South Africa.

African countries where Gynaikothrips ficorum has been reported

The species Gynaikothrips ficorum was not observed in surveys undertaken in East Africa on vegetables and associated weeds and crops.

Please click here for survey sites of all observed thrips species of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.

Bibliography

Ananthakrishnan TN (1978). Thrips galls and gall thrips. Technical Monograph, Zoological Survey of India. 1: 1-62

Bagnall RS (1909). On some new and little known exotic Thysanoptera. Transactions of the Natural History Society of Northumberland. 3: 524-540

Bennett FD (1995). Montandoniola moraguesi (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae), a new immigrant to Florida: Friend or foe? Vedalia. 2: 3-6

Bournier A (1970). Principaux types de dégâts de Thysanoptères sur les plantes cultivées. Annales de Zoologie, Écologie Animale. 2: 237-259

Crawford DL (1910). Thysanoptera of Mexico and the South II. Pomona College Journal of Entomology. 2 (1): 153-170

Denmark HA, Fasulo TR & Funderburk JE (2004). Cuban laurel thrips, Gynaikothrips ficorum (Marchal) (Insecta: Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae). Entomology Circular No. 322. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, 4 pp. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in599

Dozier HL (1926). Notes on Puerto Rican Thysanoptera. Journal of the Department of Agriculture of Puerto Rico. 10 (3-4): 279-281

Funasaki GY (1966). Studies on the life cycle and propagation technique of Montandoniola moraguesi (Puton) (Heteroptera: Anthocoridae). Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. 19: 209-211

Karny H (1912). Ueber einige afrikanische Thysanopteren. Fauna Exotica. 2 (6): 22-24

Marchal P (1908). Sur une nouvelle espèce de 'thrips' (Thysanopt.) nuisible aux Ficus en Algérie. Bulletin de la Société Entomologique de France. 14: 251-253

Moritz G (2006). Thripse. Pflanzensaftsaugende Insekten, Bd. 1, (1. Auflage). Westarp Wissenschaften, Hohenwarsleben, 384 pp. ISBN 13: 978 3 89432 8917

Moritz G, Morris DC & Mound LA (2001). ThripsID - Pest thrips of the world. ACIAR and CSIRO Publishing Collingwood, Victoria, Australia, CDROM ISBN 1 86320 296 X

Mound LA & Kibby G (1998). Thysanoptera: An identification guide, (2nd edition). CAB International, Wallingford and New York, 70 pp

Mound LA & Marullo R (1996). The thrips of Central and South America: An introduction (Insecta: Thysanoptera). Memoirs on Entomology, International, Vol. 6. Associated Publishers, Gainsville, 487 pp

Mound LA, Wang CL & Okajima S (1995). Observations in Taiwan on the identity of the Cuban laurel thrips (Thysanoptera, Phlaeothripidae). Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 103 (2): 185-190

Nickle DA (2003). A checklist of commonly intercepted thrips (Thysanoptera) from Europe, the Mediterranean, and Africa at U.S. ports-of-entry (1983-1999). Part I. Key to genera. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 105 (1): 80-99

Okajima S (2006). The Insects of Japan, Vol. 2. The suborder Tubulifera (Thysanoptera). Touka Shobo Co. Ltd., Fukuoka, 720 pp

Padrick RC (2004). Tips for Cuban laurel thrips. Ornamental Outlook. 12 (7): 40

Paine TD (1992). Cuban laurel thrips (Thysanoptera, Phlaeothripidae) biology in Southern California - Seasonal abundance, temperature-dependent development, leaf suitability, and predation. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 85 (2): 164-172

Paine TD, Malinoski MK & Robb KL (1991). Reducing aesthetic injury or controlling insect populations - dilemma of insecticide use against Cuban laurel thrips (Thysanoptera, Phlaeothripidae) in landscape-grown Ficus. Journal of Economic Entomology. 84 (6): 1790-1795

Palmer JM, Mound LA & du Heaume GJ (1989). 2. Thysanoptera, 73 pp. In Betts CR [ed.], CIE Guides to insects of importance to man. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, UK

Piu G, Ceccio S, Garau MG, Melis S, Palomba A, Pautasso M, Pittau F & Ballero M (1992). Itchy dermatitis from Gynaikothrips ficorum March in a family group. Allergy. 47 (4): 441-442

Priesner H (1939). Zur Kenntnis der Gattung Gynaikothrips Zimm. (Thysanoptera). Mitteilungen der Münchner Entomologischen Gesellschaft. 29: 475-487

Priesner H (1964). A monograph of the Thysanoptera of the Egyptian deserts. Publications de l’Institut du Desert d’Egypte (1960). 13: 1-549

Retana-Salazar AP (2006). Variación morfológica del complejo Gynaikothrips uzeli-ficorum (Phlaeothripidae: Tubulifera). Métodos Ecologia Sistemética. 1 (1): 1-9

Wheeler C, Held DW & Boyd Jr. DW (2006). Morphological differences in between two gall-inducing species, Gynaikothrips uzeli and Gynaikothrips ficorum. Proceedings of the Southern Nursery Association Research Conference (Section 3 - Entomology). 51: 153-155

zur Strassen R (1968). Ökologische und zoogeographische Studien über die Fransenflügler-Fauna (Ins., Thysanoptera) des südlichen Marokko. Abhandlungen der Senkenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft. 515: 1-125

----

Web links

Mound´s Thysanoptera pages

Thysanoptera Checklist

ICIPE Thrips survey sites

UNI Halle & Thrips sites

Thrips of California